Quentin’s research uses big, open data and statistical and theoretical models to understand how communities of living things function and how humans’ activities affect them. As an ecologist, he aims to test ecological theory about how the physical environment and interactions among organisms combine to create the biodiversity patterns we see on the landscape. As an environmental scientist, he is using data and models from ecology and economics to quantify the environmental impact of food loss and waste in the United States and determine what policies we should implement to reduce food waste and mitigate the overall burden of the food system on the environment.

Quentin’s research is driven by big questions in environmental science and ecology. Click on one to learn more.

What is the impact of food production on the environment, and how can we reduce it?

How do species coexist?

What drives biodiversity across scales?

How do individual organisms’ traits shape natural communities?

How does global change affect living communities along natural gradients?

What is the impact of food production on the environment, and how can we reduce it?

Food waste reduction and diet shifts to protect global biodiversity. Our most recent work, published in PNAS explores the connections between the food we (people in the USA) eat and harmful impacts to biodiversity both domestically and around the globe. We found that the American diet threatens hundreds of plant and animal species with global extinction. This is because of the large amount of meat, dairy, and aquaculture-raised fish Americans consume, the specialty crops they import from global biodiversity hotspots in the tropics, and because of the high levels of food waste generated by producers and consumers alike. However, reducing food waste by 50% could eliminate almost 20% of this negative impact on global biodiversity, almost as much as would be attained by drastically changing the average American diet to a highly plant-based one. This work inspired a commentary in PNAS, a feature article by Quentin, and was written up in several other media outlets (click here to read more).

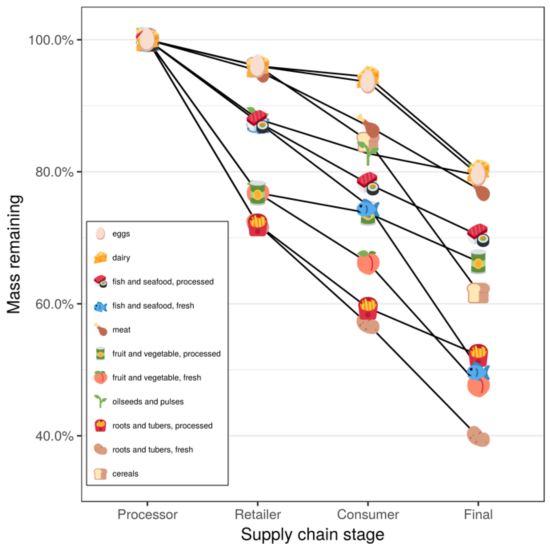

Planning food waste reduction to reduce environmental impacts. To maintain human life, it is necessary to use land, water, soil, and energy, and to place some burden on ecosystems around the globe. However, 30% to 50% of the food produced at such a steep environmental cost is wasted — this is a trademark of our inefficient food system and our culture of abundance and extravagance. Globally, six garbage trucks full of edible food are wasted every second, roughly corresponding to the weight of 10000 aircraft carriers annually — or 2700 Empire State Buildings — or 150 Great Pyramids of Giza. For another visceral comparison, the average American citizen is responsible for roughly his or her own weight in food waste each year. Read more in-depth thoughts on food waste on Quentin’s blog or take a look at recent papers we’ve published — a prioritization of food waste reduction strategies, a food supply chain modeling study, a discussion of the relationship between food waste and water scarcity, and a synthesis paper.

Quentin’s work on the food system began with a focus on the food waste problem as part of a research team based at SESYNC in Annapolis, Maryland, USA and led by Mary K. Muth, head of nutrition and policy research at RTI International. Since then, Quentin has broadened his food system research to encompass broader questions of sustainability, addressing the implications of shifting diets to make our food consumption healthier for ourselves and less damaging to the environment. Quentin’s latest work tackles the interrelated impacts of food waste and unsustainable diets. It also includes an estimate the “biodiversity footprint” of food, because food we consume in one place represents a virtual transfer of biodiversity threat from the place the food was produced to the place where it is bought and eaten. A paper on this is currently in review — check back soon!

Quentin’s food waste research uses an environmentally-extended input-output model developed by the U.S. EPA to calculate its environmental footprint. The footprint includes the land, water, energy, and chemicals that are contained in wasted food and the pollution and loss of biodiversity it causes. Finally, the team is evaluating a number of recently proposed food waste reduction solutions to see which ones are the cheapest to implement and the most effective at reducing the burden of the food system on the environment. Preliminary findings show that interventions aimed at preventing food waste before it occurs are far more cost-effective at reducing the environmental burden of food waste than efforts to repurpose or divert already existing waste. However, with limited funds to invest in food waste reduction, there may be tradeoffs among components of the environmental footprint — investing in reducing consumer-level food waste may reduce more total greenhouse gas emissions along the supply chain, while investing in reducing agricultural and processing waste may yield a greater net reduction in land and water use without changing the direct emissions footprint much. The ultimate goal is to identify and create incentives to reduce food waste, and to determine how we can get producers, processors, and consumers to act in their own best interest by preventing food waste.

How do species coexist?

Following from the observation that species diversity varies across space, especially as you go toward the equator, ecologists think that species’ niches may determine how many, and what kind, of species can coexist in a local community. Quentin has worked on several projects testing niche theory with big species datasets.

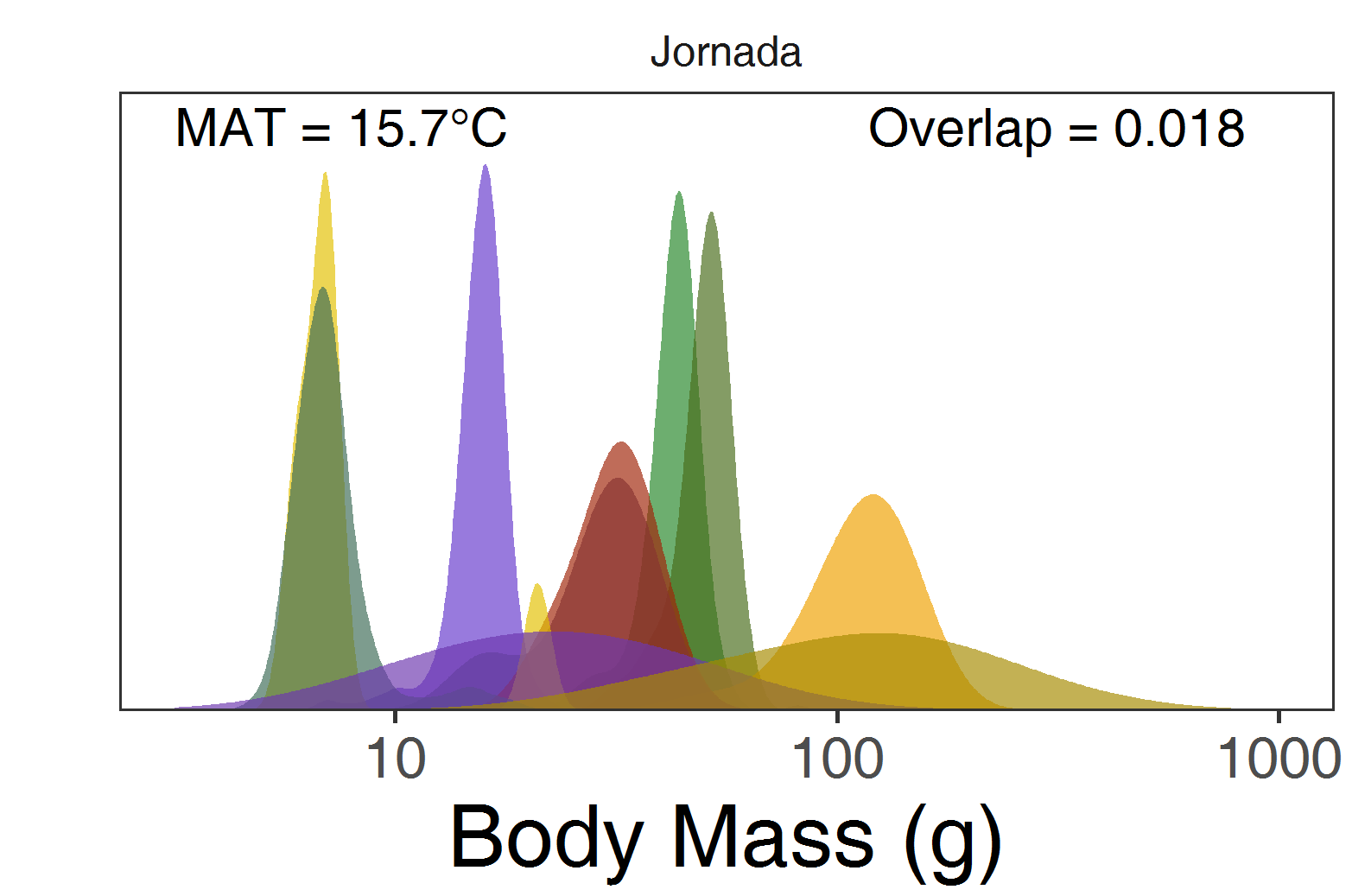

Rodent niches across the continent. Using a dataset of rodent communities and traits collected at the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON) sites, Quentin and colleagues developed a novel method to measure niche overlap among co-occurring species and ask whether overlap patterns differ along environmental gradients. Read more about this study in our publication in Ecography.

Bird niches across the globe. Using a dataset of bird specimens and their body masses collected around the globe, Quentin and colleagues explored the idea that species closer to the equator have different constraints on their niche breadth than species in the temperate zone. Read more about this study in our publication in Biology Letters.

What drives biodiversity across scales?

Why are there so many species? Why do they live where they do? Why are there more in some places than others? What consequences will ongoing human-caused global change have for patterns of diversity? These are the questions that keep community ecologists up at night. Quentin is working on tackling these questions, and more, through a variety of projects:

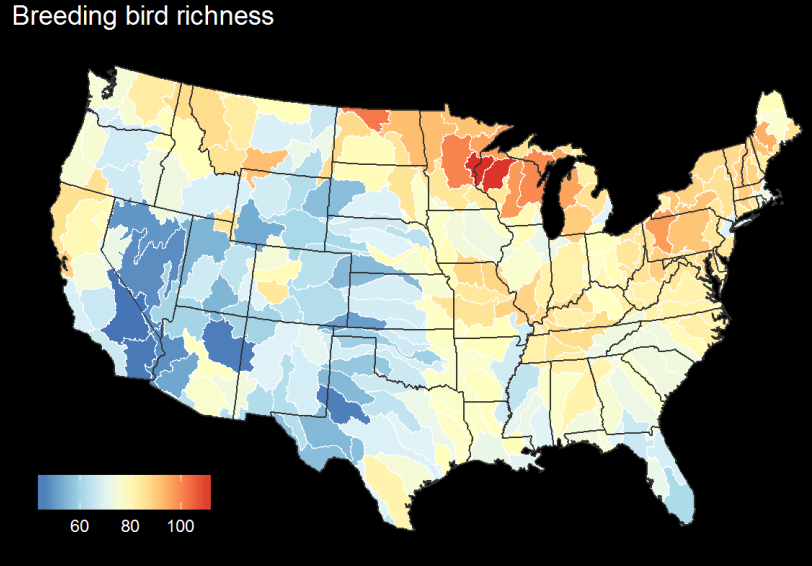

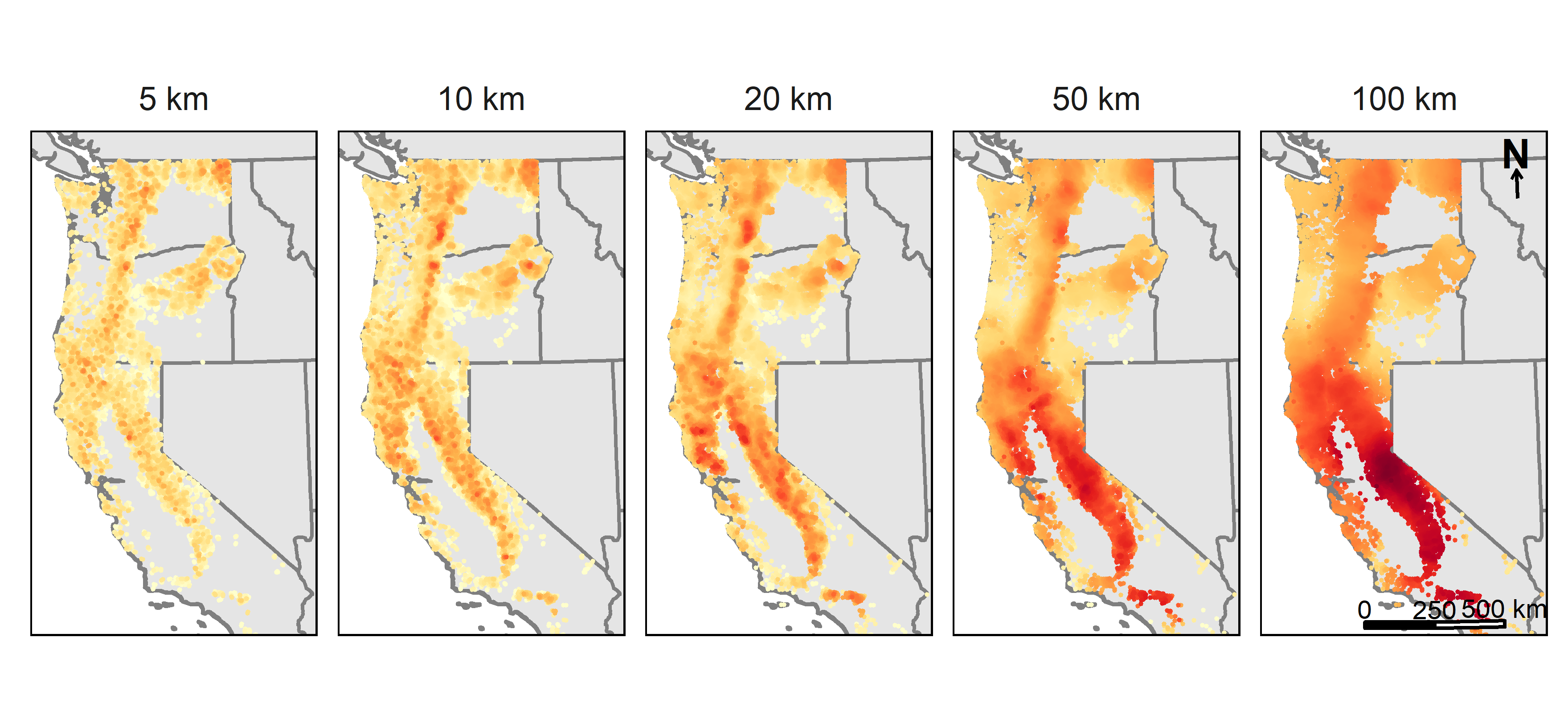

Using remote sensing to link biodiversity and geodiversity. In collaboration with researchers from NASA and other academic institutions, Quentin is exploring the relationship between biodiversity and geodiversity (variation in the physical environment) from small to large spatial scales. The research team is connecting biodiversity datasets with huge scope in space and time, including the Forest Inventory and Analysis dataset and the Breeding Bird Survey dataset, with remote sensing data from NASA including elevation, climate, geology, and human land use. Combining data with disparate spatial scales requires special techniques of analysis; through this project, the team is advancing the cutting edge of geospatial statistics. Read about patterns of bird and tree biodiversity in a publication in Global Ecology and Biogeography and the accompanying conceptual paper.

Land and water biodiversity at nested watershed scales. Biodiversity research in land-based ecosystems and freshwater ecosystems has largely been two separate efforts. With a team of interdisciplinary researchers, Quentin is exploring the mechanisms relating land and freshwater biodiversity. In this project, the team is looking at biodiversity at the watershed level. Since watersheds are naturally nested, this lends itself to multiscale comparisons: the team hypothesizes that the strength of linkages between land and water biodiversity will depend on watershed scale. The team has a publication in review — check back soon!

How do individual organisms’ traits shape natural communities?

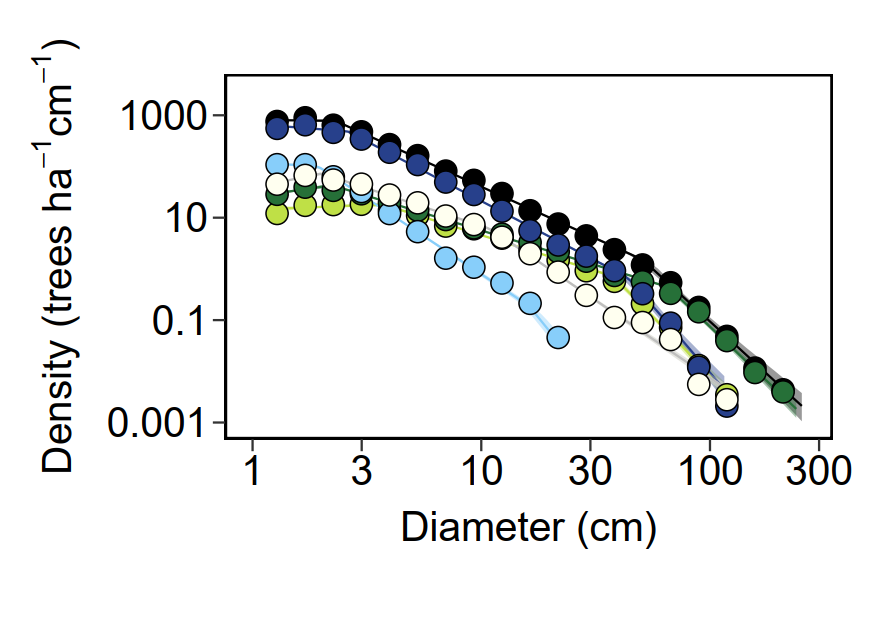

Demographic traits and metabolic scaling in forests. How is energy distributed in living systems, and how have those patterns changed over time? The answer to that question has consequences for how we understand the relationship between species diversity and the functioning of ecosystems. In a project led by fellow postdoc John Grady, Quentin is asking how growth-mortality tradeoffs and light competition affect how energy is divided among trees of different sizes, within and among functional groups and species, in tropical forests. Read our preprint on the bioRxiv.

Predicting community composition from individual organismal traits. The functional trait literature in ecology is replete with references to the “Holy Grail”–the elusive goal of predicting what species will be found in a given place, knowing only the traits of species present in the region and the environmental conditions at the location. Quentin has done work to refine these models, but so far their predictive power seems to be lacking in some systems. Read more about this study in our publication in Journal of Vegetation Science.

How does global change affect living communities along natural gradients?

Plant ecology in the field. Quentin’s original approach to tackling big ecological questions (as a Ph.D. student at the University of Tennessee) involved making observations and conducting experiments in the field. Through these studies, he observed how natural systems respond to global change and how that response is determined by baseline environmental conditions and by the functional properties of local communities of organisms. We have a good understanding of how physical aspects of the environment affect living things, and how that relationship is changing due to human activities.

However, we still don’t understand how this relationship varies from place to place and how it is modified by interactions among organisms that differ in their traits. To address these questions, Quentin developed and ran field studies in and around the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in western Colorado. He simulated warming, nitrogen deposition, and loss of dominant species at study sites at different elevations. Quentin also explored trait variation within and among species in nature and in simulated data — read more about this work in publications in Functional Ecology and Oikos. The warming and species loss study conducted across elevations shows that loss of dominant plant species has a bigger effect than warming on the remaining plant community, but only at low elevations where plants become dominant due to competitive traits.