Why do we waste so much food?

Published:

Food waste is the trademark problem of our culture of abundance. Pouring huge proportions of our precious land, soil, water, and energy resources into producing food, and inflicting damage on the environment in the process, is necessary to maintain human life. But constructing an inefficient food system that throws out about 40% of the food we produce every day — that is a trademark of our culture of abundance, profligacy, and waste. It’s hard to comprehend the scale of the problem without some comparisons, so here goes:

- Six garbage trucks full of edible food are wasted every second.

- The average American citizen is responsible for roughly his or her own weight in food waste each year.

- Some estimates of global food waste come out to roughly the weight of 10000 aircraft carriers annually — or 2700 Empire State Buildings — or 150 Great Pyramids of Giza — take your pick.

This isn’t just tossing out a Tupperware of spoiled leftovers in your fridge, though that’s part of it. It includes waste from the entire length of the food supply chain: edible produce that does not meet strict cosmetic grading standards, meat that is spoiled in transit to a wholesaler and is trashed straight from the loading dock, or excess retail inventory that reaches its expiration date and has to be dumped. When we waste food, we are throwing out much more than the volume of food that is physically in the Dumpster. Taking a life-cycle perspective, you can see that the sum total of resources involved in producing that food — like fertilizer and land to grow it, fuel to harvest and transport it, and energy to process and cook it — also go to waste.

Everyone should be on board with any plan that could reduce food waste, which would relieve pressure on the environment, save money, and reengineer the very structures that underpin our civilization, making it more sustainable. And it seems like they are — politicians from both sides of the aisle are tripping over each other to set goals and form initiatives to reduce food waste. It’s a difficult problem but one that we might be able to solve. But I’m not sure it’s really as simple as it seems.

In the last few months I’ve begun work on a project that is taking my research in a new direction. From my new base at SESYNC in Annapolis, Maryland, I am working with a group of colleagues on the food waste problem. First, we aim to gather as much data as we can on food waste in the United States. Next, we are calculating its environmental footprint, which includes both the land, water, energy, and chemicals that are contained in wasted food and the pollution and loss of biodiversity it causes. Finally, we are evaluating a number of recently proposed food waste reduction solutions to see which ones are the cheapest to implement and the most effective at reducing the burden of the food system on the environment.

I’m glad to be involved in work on the food system that has the potential to enable a transition to a more sustainable society. Unfortunately, the more I study the problem, the more difficult it looks. Dozens of organizations have proposed solutions for the food waste problem. Many of them assume that we can reach a “win-win” situation by reducing food waste, because reducing waste will increase efficiency and save money at the same time as it saves the environment. That might be true to some extent, but it ignores the issue that there wouldn’t be such a massive amount of waste if there weren’t some serious incentives to generate that waste.

Examples of incentives to create food waste abound. For one, studies of consumer psychology show that we buy more when grocery stores bombard us with textures, colors, and smells. All those groaning shelves of produce and bread just inside the front door of the supermarket, topped up almost around the clock, aren’t all even intended to be sold and eaten. Much of it is just there to lure in shoppers. Farmers also have an incentive to overproduce as insurance that they can fulfill their advance contracts with buyers even if they lose some crop – this results in lots of produce left to rot in the field. Or to bring it to the household level, there is strong cultural pressure to provide abundant food to guests, even if we know there’s no way it will all be eaten. The list goes on. Producers and processors are already motivated by their desire to maximize profit, and consumers are always looking to save a buck. It’s not easy to identify inefficiencies that they haven’t already taken into account.

All of that sounds pessimistic, but I think the first step to solving the problem of perverse incentives is to identify them. We can’t find a cure for this disease without giving it a name. My plan is to use large-scale models of the entire US food system to find sectors of the economy and geographical regions where incentives do exist to reduce food waste, and to determine how we can get producers, processors, and consumers to act in their own best interest by preventing food waste before it occurs. When it comes to food waste, just like all the other wicked problems facing our society, there is no silver bullet but with the right information we can make a difference.

I’m hoping that this blog post will be the first in a series. In future posts I will write more about some of the specific solutions that are proposed or already underway to reduce food waste, talk about the results we’re finding, share some new ideas for how we can solve the food waste problem, and provide links to resources to learn more about the organizations dedicated to reducing food waste. Here are a few links for starters:

- ReFED: Rethink food waste through economics and data. This organization has come up with a “road map” to reduce food waste by 20% in the United States. They have a lot of details on different ways to reach that goal.

- World Wildlife Fund: WWF’s initiative on reducing food waste is a great example of how they’ve broadened their focus from protecting specific species to promoting sustainable use of natural resources overall.

- Leanpath: Our SESYNC collaborator Steve Finn works for this company that helps corporations and other institutions reduce their food waste. Check out their food waste blog.

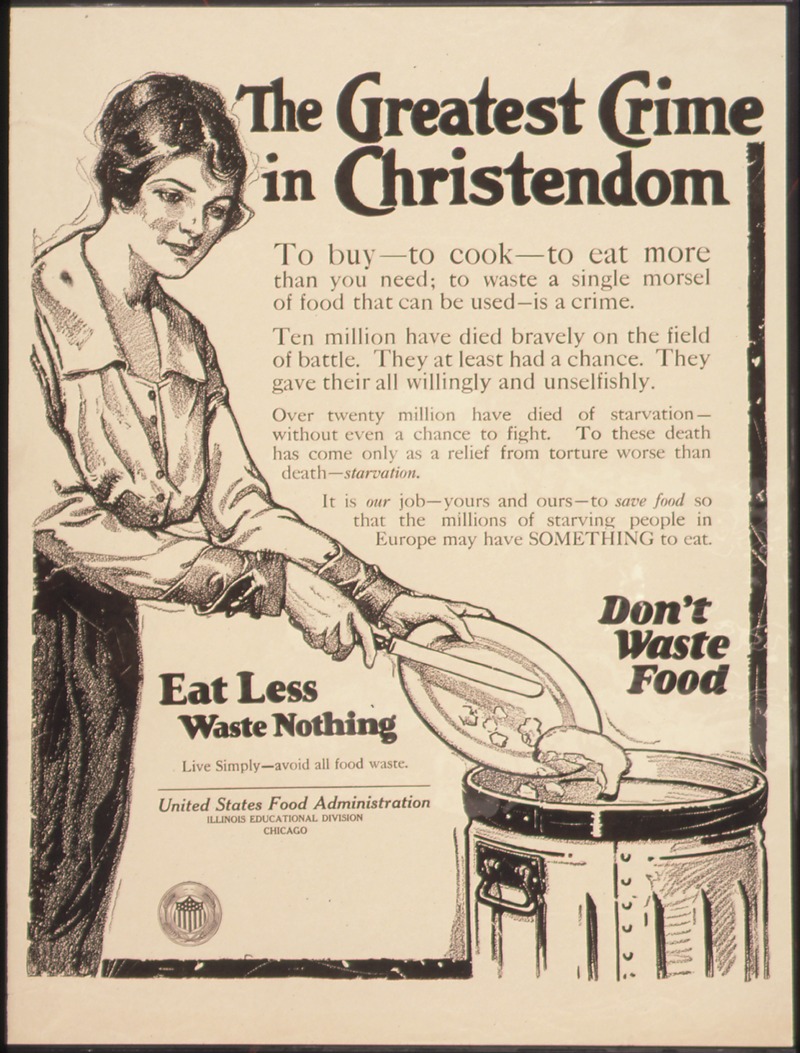

Image credits: Pile of food waste - By Taz - flickr, CC BY 2.0, wikimedia; Garbage truck - CC BY-SA 3.0, wikimedia; 1917 poster - By Unknown or not provided - U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Public Domain, wikimedia

Leave a Comment